Every summer, as the sun warms the grass courts of the All England Club, history whispers beneath the soles of every player who walks onto Wimbledon’s hallowed lawns. Among those footsteps are echoes of women who, for over a century, have pushed boundaries—not just in sport, but in society.

The history of women at Wimbledon is not just about tennis. It’s about access, recognition, equality, and enduring excellence. It is a narrative of athletes who transcended their time, defied gender norms, and turned a genteel pastime into a battleground of grit, elegance, and ambition.

Maud Watson 1884-5

The Origins: Tennis, Class, and Victorian Constraints (Late 19th Century)

Wimbledon was born in 1877 as a men’s-only tournament, reflecting the rigid gender dynamics of Victorian Britain. Lawn tennis had become fashionable among the upper classes, especially as a social sport for women—more a courtship ritual than athletic pursuit. While men competed, women in long dresses hit underhand serves at garden parties.

But the tide shifted in 1884, when Wimbledon introduced the Ladies’ Singles Championship—only seven years after the first Gentlemen’s Singles. This was a bold and surprising move by the All England Club. While framed as an expansion of entertainment, it was also a nod to the growing movement for women’s participation in sport, education, and public life.

Only 13 women entered that inaugural event. The winner, Maud Watson, a 19-year-old vicar’s daughter from Warwickshire, defeated her older sister Lilian in straight sets, wearing a corset and floor-length white dress. It was a victory both athletic and symbolic.

Charlotte Cooper

The Early Pioneers: Elegance and Endurance (1890s–1920s)

For decades, the women's game was defined as much by fashion as by finesse. Corsets, long sleeves, and flowing skirts restricted movement, yet women persisted. The sport was demanding, and matches could be grueling—especially without the ability to hit overhead serves or move freely.

During this era, champions like Charlotte Cooper dominated. Cooper won five Wimbledon titles between 1895 and 1908. She was also the first woman to win Olympic gold in tennis in 1900, breaking barriers at a time when many still questioned whether women should compete in sports at all.

She played with elegance and calm, but also with a tactical mind and fierce resolve—traits often undervalued in women’s athletics at the time.

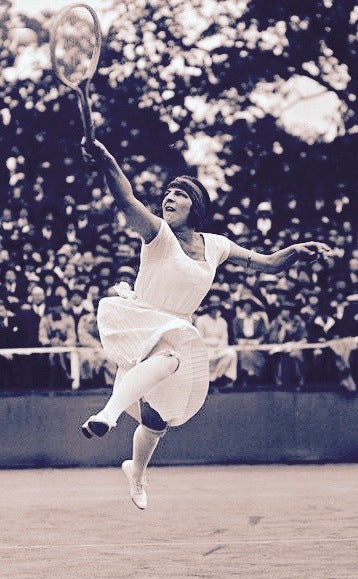

Suzanne Lenglen 1922

Suzanne Lenglen: Tennis’ First Female Superstar (1920s)

Then came Suzanne Lenglen.

A Frenchwoman with flair, confidence, and a forehand like a whip, Lenglen revolutionized women’s tennis. She played with an attacking style previously unseen in the women’s game. Nicknamed “La Divine,” Lenglen captivated crowds with her bold strokes, dramatic entrances, and signature headbands.

In a sport of decorum and restraint, she was unapologetically flamboyant. She wore shorter skirts, moved with balletic grace, and carried herself like a performer. Between 1919 and 1925, she won six Wimbledon singles titles—many without dropping a set.

Her success forced Wimbledon and the tennis world to take women's tennis seriously—not as an add-on to the men’s game, but as its own thrilling spectacle. Lenglen showed that women’s matches could fill stadiums, sell newspapers, and make headlines.

Helen Wills Moody 1932

The Interwar Years and Wartime Pause (1930s–1940s)

The 1930s saw continued growth in the women’s game, with dominant champions like Helen Wills Moody of the United States, who won eight Wimbledon titles between 1927 and 1938. Moody was a stark contrast to Lenglen—stoic, emotionless, and clinical. Yet her dominance only heightened the prestige of the women’s draw.

World War II, however, paused Wimbledon from 1940 to 1945. When it resumed in 1946, a war-weary Britain was ready for inspiration. Women’s tennis offered exactly that.

Althea Gibson

The Golden Era: Postwar Icons and Global Growth (1950s–1970s)

The 1950s and 1960s ushered in a golden era of women’s tennis, with global talent emerging from Australia, the U.S., and across Europe. Champions like Althea Gibson and Margaret Court began to reshape the sport.

In 1957, Althea Gibson became the first Black woman to win Wimbledon, a historic triumph that transcended sport. Coming from Harlem, New York, Gibson’s victory was a cultural earthquake. Her Wimbledon title wasn't just a win for tennis—it was a win for racial integration and representation.

The 1960s belonged to Australia’s Margaret Court, who would go on to win three Wimbledon titles and a record 24 Grand Slam singles titles overall. Her era marked a shift toward more powerful, athletic women’s tennis.

But even as the sport grew, inequality remained stark. Women still received less prize money than men—sometimes by wide margins. Matches were scheduled earlier in the day, and media coverage was often patronizing.

Billie Jean King 1970

Billie Jean King: Equality, Advocacy, and Victory (1960s–1970s)

If one woman embodies the fight for equality in tennis, it is Billie Jean King.

A fierce competitor and social activist, King won six Wimbledon singles titles and 20 Wimbledon titles overall (including doubles and mixed)—a record unmatched to this day. But her greatest contribution was off-court.

In 1973, the same year she beat Bobby Riggs in the famous "Battle of the Sexes," King founded the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) and demanded equal prize money. That year, the U.S. Open became the first Grand Slam to offer equal pay to men and women—Wimbledon, however, would take decades longer.

King once said, “Tennis is just a platform to change the world.” Her activism lit a fire that has shaped every generation since.

Martina Navratilova 1980

The Power Era: Navratilova, Evert, and the 1980s

The 1980s saw the rise of perhaps Wimbledon’s most iconic rivalry: Chris Evert vs. Martina Navratilova.

Evert, elegant and consistent, with her baseline game and calm demeanor, won three Wimbledon titles. Navratilova, athletic and aggressive, with serve-and-volley mastery, won a record nine Wimbledon singles titles—the most of any player, male or female.

Their rivalry elevated women’s tennis to unprecedented popularity. Matches between them weren’t just technically excellent—they were psychologically intense, contrasting styles and personalities. Navratilova, an openly gay, defector from communist Czechoslovakia, also became a cultural symbol of courage and individuality.

During this time, women’s tennis at Wimbledon began attracting audiences equal to men’s finals. The quality of play, the emotional stakes, and the athleticism spoke for themselves.

Venus and Serena Williams 1993

Modern Icons: Graf, the Williams Sisters, and Equality at Last (1990s–2000s)

The 1990s introduced Steffi Graf, who dominated with power and precision. She won seven Wimbledon titles, her forehand a weapon of unmatched ferocity. Graf’s professionalism and focus set new standards for training and mental toughness in the women’s game.

But the 2000s belonged to two sisters from Compton, California: Venus and Serena Williams.

In 2000, Venus Williams won her first Wimbledon title and followed it up with another in 2001. Her serve was historic—the fastest the women’s game had ever seen.

Then came Serena.

Between 2002 and 2016, Serena Williams won seven Wimbledon singles titles, her combination of power, agility, and intelligence redefining what women’s tennis could be. With 23 Grand Slam singles titles overall, Serena not only became one of the greatest athletes of all time—but a global icon for Black excellence, motherhood, and resilience.

In 2007, thanks in large part to persistent advocacy from Venus Williams and the WTA, Wimbledon finally awarded equal prize money to men and women. The last Grand Slam to do so, its decision was both historic and overdue. That same year, Venus claimed her fourth title—winning not just the match, but the moral battle.

The Present Day: Depth, Diversity, and New Heroines

Today, women’s tennis at Wimbledon is deeper and more unpredictable than ever. Champions come from all corners of the globe—Simona Halep, Ashleigh Barty, Elena Rybakina, Markéta Vondroušová, and others have lifted the Venus Rosewater Dish in recent years.

The athleticism is astounding, the competition fierce, and the stories richer than ever.

Moreover, Wimbledon has embraced women’s tennis not just as tradition, but as a key part of its identity. From equal prize money to prime scheduling, the tournament has recognized that the future of tennis is not gendered—it is inclusive, competitive, and global.

More Than a Game

The history of women at Wimbledon is a history of struggle and triumph. It is a story of how a handful of women in corsets hitting soft lobs on manicured lawns laid the groundwork for generations of fierce, athletic, and unapologetically ambitious champions.

From Maud Watson to Serena Williams, Wimbledon has been a stage for women to make history, demand equality, and inspire millions. The green grass has seen fashion and politics, heartbreak and glory, silence and cheers—but always, it has borne witness to the remarkable evolution of women’s tennis.

As Wimbledon continues into its next chapter, one thing is certain: the legacy of its women champions will always be central to its soul.