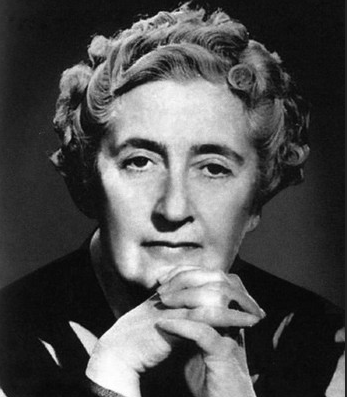

Few writers have left as indelible a mark on modern literature as Agatha Christie. Over a career spanning more than five decades, she not only transformed the detective story into a global art form but also became, by some estimates, the best-selling novelist in history, with more than two billion copies of her books sold worldwide. Yet beyond the carefully plotted murders and ingenious denouements lies the story of a woman whose own life contained mystery, resilience, and reinvention.

Early Years: Edwardian Childhood and Self-Education

Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller was born on 15th September 1890, in Torquay, a seaside resort in Devon, England. She was the youngest of three children born to Frederick Alvah Miller, an American stockbroker, and Clara Boehmer Miller, an Englishwoman of genteel descent. The Miller household was typical of the middle-class prosperity of late Victorian and Edwardian Britain.

Christie’s upbringing reflected the conventions of her social class: she was educated primarily at home, under her mother’s supervision, with little formal schooling until her teens. Clara encouraged her daughter’s imagination, fostering a love of reading, storytelling, and music. Agatha learned the piano and considered a musical career, though crippling shyness and performance anxiety thwarted that ambition.

Her father’s death in 1901, when she was just eleven, cast an early shadow. The loss brought both emotional and financial strain, and it marked the first of several pivotal bereavements in her life. Yet these early experiences of isolation and introspection may also have nurtured the imaginative self-sufficiency that would later define her writing.

At nineteen, Christie traveled to Paris, where she studied voice and piano. There she encountered the cosmopolitan atmosphere of pre-war Europe, a world that would soon vanish. By her own account, she led a rather sheltered life until her early twenties, when the turbulence of World War I abruptly altered her course.

War, Work, and the Birth of a Writer

When Britain entered the First World War in 1914, Christie, like many women of her generation, found herself thrust into new responsibilities. She joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), serving first as a nurse and later as a dispenser at a hospital in Torquay.

This wartime service provided Christie with two invaluable forms of education. First, it exposed her to a wide range of human suffering and endurance, a crucible that deepened her understanding of character and motive. Second, her training in pharmaceuticals and poisons furnished her with the technical knowledge that would later underpin the ingenious murder methods in her fiction.

It was also during this period that she met Archibald (“Archie”) Christie, a dashing Royal Flying Corps officer. The pair married on Christmas Eve, 1914, while he was on leave. Their marriage, passionate at first, would prove fraught with difficulty, a reflection, perhaps, of the shifting gender and social dynamics of the post-war world.

Encouraged by her sister Madge to write a detective story, Christie began her first novel during the war. Drawing on her pharmaceutical experience, she created a narrative centered on poisoning and deduction. After several rejections, The Mysterious Affair at Styles was finally published in 1920. It introduced Hercule Poirot, the fastidious Belgian detective who would become one of the most recognizable figures in popular fiction.

The Roaring Twenties and the Rise of the Queen of Crime

The 1920s were years of both artistic triumph and personal turmoil. With Styles and subsequent novels, Christie quickly established herself as a leading figure in the burgeoning detective-fiction genre, alongside contemporaries such as Dorothy L. Sayers and G. K. Chesterton.

Her early novels, The Murder on the Links (1923), The Man in the Brown Suit (1924), and The Secret of Chimneys (1925), reflected the optimism and disillusionment of interwar Britain. They blended genteel domestic settings with global intrigue, mirroring the cultural tensions of an empire in decline. Yet beneath the success, Christie’s private life was deteriorating. Her beloved mother, Clara, died in 1926, a loss that devastated her. Her marriage, too, was in crisis: Archie had fallen in love with another woman, Nancy Neele, and demanded a divorce. The dual trauma of bereavement and betrayal precipitated the most enigmatic episode of Christie’s life.

The Disappearance of December 1926

On the night of 3rd December 1926, Agatha Christie left her Berkshire home and vanished. The next morning, her abandoned car was discovered near Newlands Corner, Surrey. Inside was her driver’s license, an overnight bag, and her fur coat but no sign of the author herself.

The ensuing days gripped Britain in collective suspense. Newspapers printed daily updates, and thousands of volunteers joined police in a massive search. Even fellow authors, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, became involved; Doyle famously consulted a medium, giving her one of Christie’s gloves in hopes of spiritual guidance.

For eleven days, Christie’s whereabouts remained a mystery. Then, on 14th December, she was discovered at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel in Harrogate, where she had registered under the name “Mrs. Teresa Neele”, the surname of her husband’s lover.

Christie later claimed to have suffered from amnesia, unable to recall how she arrived there or why. Medical experts at the time supported the diagnosis of a nervous breakdown brought on by stress and shock. Others have speculated that her disappearance was a deliberate act of revenge, an unconscious flight from emotional trauma, or even a calculated publicity stunt.

Christie herself never explained the incident publicly, even in her Autobiography. The episode remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of literary history, eerily fitting for a woman whose career revolved around the art of concealment and revelation.

Reinvention: The Archaeologist’s Wife

Following her divorce from Archie in 1928, Christie embarked on a period of travel and self-renewal. In 1930, while visiting an archaeological site at Ur in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), she met Max Mallowan, a young archaeologist thirteen years her junior. They married later that year, a union that would prove happy and enduring until her death.

Her marriage to Mallowan opened a new chapter in her life, one defined by adventure, intellectual curiosity, and cultural exploration. Accompanying her husband on excavations across the Middle East, Christie immersed herself in the landscapes and peoples of Syria, Iraq, and Egypt. She photographed sites, catalogued artifacts, and adapted to the rigors of desert life with remarkable resilience.

These experiences profoundly influenced her writing. Novels such as Murder in Mesopotamia (1936), Death on the Nile (1937), and Appointment with Death (1938) bear the imprint of her travels, themes of displacement, cultural encounter, and the ancient world’s mysteries woven into her tightly plotted narratives.

From a historian’s perspective, this period also reflects Britain’s interwar fascination with archaeology, empire, and the exotic “East.” Christie’s fiction captured the era’s blend of curiosity and imperial confidence, while her own presence at digs signaled the growing (if still constrained) participation of women in scholarly and scientific endeavors.

War Again: The 1940s and The Mousetrap

When war returned in 1939, Christie, now approaching fifty, once again offered her services. She worked as a dispenser in the University College Hospital in London, deepening her already formidable knowledge of poisons, knowledge that found its way into works such as Sparkling Cyanide (1945).

The war years also saw her create some of her most enduring stories, including N or M? (1941) and The Body in the Library (1942). These novels subtly engaged with wartime anxieties, spies, sabotage, hidden identities, set within the reassuringly ordered structure of the detective puzzle.

Her most remarkable post-war achievement, however, was theatrical rather than novelistic. In 1952, her play The Mousetrap opened in London’s West End. It would become the longest-running play in theatrical history, closing only temporarily during the COVID-19 pandemic more than six decades later.

By the early 1950s, Christie was not merely a novelist but a cultural institution. Her detectives, Poirot with his “little grey cells,” and Miss Jane Marple with her shrewd village wisdom had entered the global imagination.

The Art of Detection: Craft, Character, and Worldview

Christie’s success cannot be explained solely by her plots, however ingenious. Her fiction offered readers of the twentieth century something deeper: a ritual of reassurance.

In the disordered world of modernity, marked by war, social upheaval, and moral uncertainty, Christie’s mysteries restored order. A crime disrupted the peace; a detective, embodying logic and reason, reconstructed the truth; justice, or at least resolution, was achieved. This structure, as literary scholars have observed, mirrored the anxieties and aspirations of interwar Britain.

Her settings, English country houses, provincial villages, luxury trains, archaeological sites, served as microcosms of a changing society. Within them, she dissected the manners, prejudices, and ambitions of the middle and upper classes. Beneath the veneer of civility lay greed, jealousy, and deceit.

Christie’s prose was famously economical. She avoided the psychological depth of modernists like Virginia Woolf, preferring clarity and pace. Yet her understanding of human motive was acute. Her villains are not monsters but ordinary people pushed by emotion or circumstance, a moral realism that may explain her enduring appeal.

Late Years and Literary Authority

The 1950s and 1960s consolidated Christie’s position as Britain’s preeminent crime writer. She received the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 1971 and was appointed Dame Commander for her contributions to literature.

Though she slowed her writing in later years, she continued to publish until the mid-1970s. Her final novels, Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case and Sleeping Murder, were written during World War II but withheld until near the end of her life, providing a fitting farewell to her most beloved detectives.

Christie’s private life during this period was stable and content. She and Max Mallowan divided their time between their London residence and Winterbrook House in Oxfordshire. Visitors described her as warm yet reserved, more interested in conversation about archaeology and gardening than fame.

She died peacefully on 12th January 1976, aged 85. Her husband followed two years later. They are buried together at St. Mary’s Church, Cholsey, near Wallingford, a modest resting place for one of the most widely read authors in history.

The Enduring Enigma

Nearly half a century after her death, Agatha Christie remains an enigma. Her novels continue to sell millions; her plays fill theatres; her detectives stride across television screens. Yet the woman behind the words, private, disciplined and elusive, defies easy understanding.

Perhaps that is fitting. For Christie, mystery was not simply a genre but a worldview: life itself was a series of puzzles, misunderstandings, and concealed motives. Her gift was to transform that uncertainty into art.

From her Edwardian girlhood to her final days as Dame Agatha, she navigated a century of upheaval with the same composure and curiosity she granted her detectives. Her work endures not merely because it entertains, but because it affirms something timeless, the human desire to know, to uncover, to make sense of the inexplicable.

In the end, Agatha Christie’s greatest mystery is not the fate of a fictional victim or the identity of a clever killer, but the story of herself: a woman who vanished for eleven days, returned without explanation, and spent the rest of her life revealing, on paper, the secrets of others, while keeping her own forever veiled.